Water is a crucial resource - not just to sustain life but entire nations through supporting industry, agriculture, and trade. Accessing water, however, is in reality far from a simple feat, owing to discrepancies in spatial distributions of water resources, man-made demarcations, and societal demand, rendering water an easily politicised and contested resource.

Welcome to my blog, where I explore the theme of water and politics in relation to development. I will examine just how inextricable politics and power relations are to any discussion of water access, focussing specifically on Africa. Few places beyond this continent exemplify the politics of water access more clearly: despite holding abundant freshwater at 9% of global supply (Gaye and Tindimugaya, 2019), a combination of colonial legacies and natural environmental landscape factors mean that Africa is today especially vulnerable to water conflict. In this introductory post, I will explore both these factors in a bit more depth to show how they contribute to the continent's water challenges.

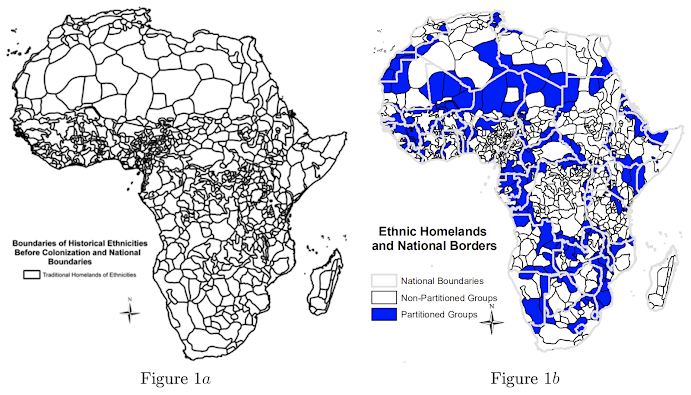

If you look at a map of modern-day Africa, you'll notice a dozen or so stretches of simple straight lines separating some sovereign nations. This was not a coincidence but rather a direct consequence of the Berlin Conference of 1885, where European and western colonial powers met to 'carve up' Africa armed with very limited knowledge of Africa themselves. In many cases, physical features like rivers and river basins were arbitrarily used as the basis of partitions, without consideration of how these natural resources and commons have historically been jointly used and shared, nor the fact that their users are one of the most ethnically diverse globally (Green, 2012; Figure 1). Even following independence in the mid 20th Century, many nations retained these borders and their associated water use agreements, extending and exacerbating issues of water rights and access, and deepening the entanglement between access to water and politics. Today, despite new water use agreements being drawn up, colonial-era agreements are sometimes still being used by countries if and when it favours their water access (Mwilima, 2021; Tekuya, 2020). For example, the Nile River's two upstream riparians - Egypt and Sudan - cited British colonial agreements allocating its water to both states and awarding Egypt veto rights to any Nile River projects, serving as a major source of conflict in the Nile Basin particularly with the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a topic to which I hope to return in later posts.

|

| Figure 1: National borders (Figure 1b white lines) of contemporary Africa have little regard for the various ethnic groups and associated natural resources such as water employed by them (Source). |

|

| Figure 2: Seasonal changes in the position of the ITCZ (Source). |

Hi Adrian, it was very interesting to read about the links between environmental conditions and how they can complicate the politics of water accessibility. I am looking forward to reading more of your posts!

ReplyDeleteThanks for reading, hope you find my other posts as insightful and engaging!

DeleteA nice introductory post about the geophysical and political implications of water but also its relation to historical arrangements. Well written with good engagement with literature, with a defined scope for analysis of water politics.

ReplyDelete